“You may have the universe, if I may have Italy.” – Guiseppe Verdi

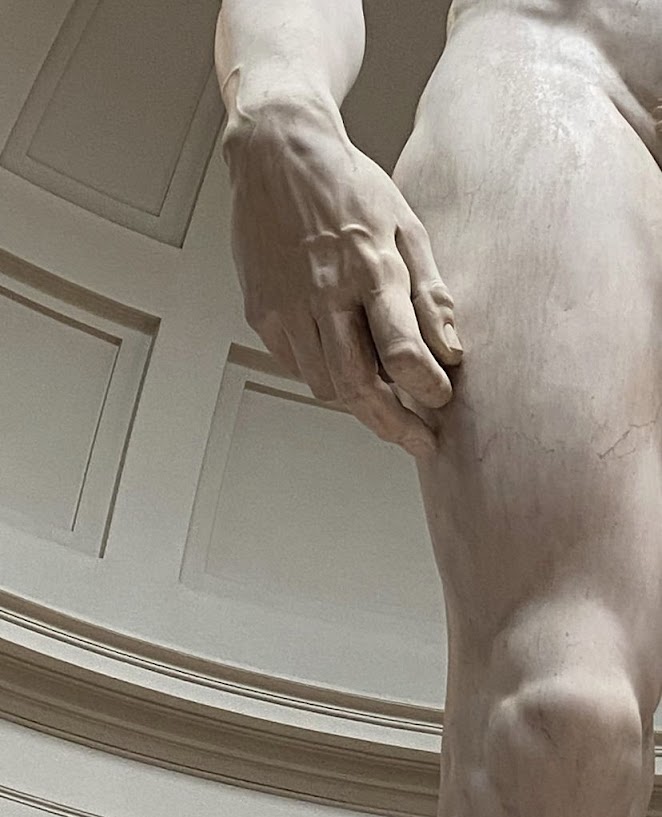

From the dazzling but functional gleaming white washing-machines adorning the balconies of small suburban apartments, to Michelangelo’s hugely sublime pristine white marble statue of David, Florence is a city of enchanting contrasts or, in the words of Salman Rushie, a world as perfect as any heaven.

The seductive allure of the Tuscan capital is extraordinary, immersive and exhaustive, so much so that it sometimes feels important to have time away from the vibrant hubbub of the city.

On a recent visit, we stayed in a beautiful apartment a bus ride away, with a perfect view to the Duomo; this sense of slight separation from the heart and soul of the historic urban centre meant that, after a two-week stay, I had not seen enough, wishing I could return to some places, such as the Uffizi, (ideally, without the crowds, so I could gaze at life’s masterpieces, untroubled by the comments and presence of others). A day spent among the red-brown buildings of medieval Siena (yes, it is where the popular pigment gained its name, and also home of the adrenaline-fulled palio horse race) was a further separation; its Piazza del Campo is said to be one of the most beautiful in Italy; it, and the narrow streets around it, provided a glorious point of contrast for my birthday. Cheers.

We used buses in Florence, the number seventeen to be precise, alighting close to the Stazione Santa Maria Novella in the centre, having never quite figured out how the tram system worked nor where they went (not terribly close to our apartment was the answer).

The buses near the apartment stopped outside the tempting local pasticceria (we succumbed more than once, for torta and a cheeky Aperol or two); buses were regular, relatively cheap, and generally not overcrowded, except for the number seven to hilltop suburb, Fiesole. Here, on a very hot, overcrowded vehicle labouring its way up the winding hill to the well-known tourist destination, an adept ‘pickpocket’ stole my wallet containing my passport and money, a reminder of the dark underbelly of any city, regardless of its overt beauty.

The Carabiniere advised (with a sad shake of his head) this naive tourist that while Florence is a friendly place, “not everyone is to be trusted, Signora” and while a trip to the British Embassy to obtain an emergency travel document is interesting, it is not top of most people’s ‘to do’ lists, mine included.

Message received and fully, retrospectively, understood. A relative made me feel slightly less foolish by telling me how he once slept on a Florentine bridge with his rucksack for a pillow. By morning, his rucksack and all within it, had gone. He had the excuse of youth, however.

Nonetheless, despite the distractions, I was glad to visit Etruscan Fiesole, with its panoramic views of Florence and the fertile Valdarno. 295 metres (968 ft) above Florence, its air of expensive exclusivity traditionally made it a getaway for the city’s upper classes, but now it exudes a relaxed tranquility for the rest of us. Notable people lived here in this wealthiest of Florentine suburbs, including the Renaissance humanist, Bocaccio (who wrote The Decameron – now on my reading pile) along with incomers Proust, Dumas, and Frank Lloyd Wright …

In 1819, it even attracted the attention of seascape supremo, Turner (goodness, that man got around) whose sketch and watercolour compared surprisingly poorly to the twenty-first century visual reality.

Florence itself is a Renaissance city packed with churches, galleries and yes, obviously people. Tourists flock here and who can blame them (us)? Rightly or wrongly, it somehow feels alive but safe.

How others describe Florence …

Divided into two halves by the River Arno, author Jennifer Coburn described Florence beautifully but succinctly, as “… like attending a surprise party every day.” I get that, as something new and visually unexpected unfolds around every corner.

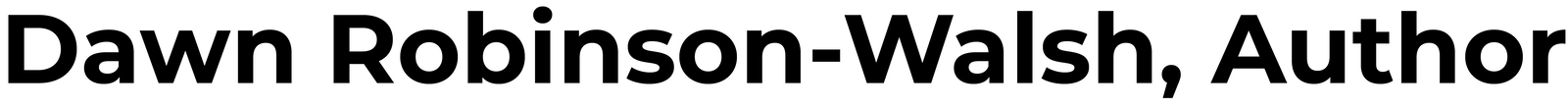

There are so many superlatives to describe Florence that people visiting in the nineteenth century were often ‘overcome’ by the city known as the centrepiece of Tuscany. I get that, too. Writer, John Ruskin, wrote in 1875, that … You will begin to wonder that human daring ever achieved anything so magnificent and that was constantly my first thought, although granted, ‘OMG’ is a tad less articulate than Ruskin’s pretty prose, but how on earth did the Florentines achieve all this with so little technical know-how? One answer is Renaissance man, Brunelleschi, who would identify an engineering problem, then invent a solution to it.

In the words of essayist, William Hazlitt (1826), Florence is like a town that has survived itself. It is distinguished by the remains of early and rude grandeur; it is left where it was three hundred years ago. Its history does not seem to be brought down to the present period. On entering it, you may imagine yourself enclosed in a besieged town; if you turn down any of its inferior streets, you feel as if you might meet the plague still lurking there … by 2023, that plague would be Covid, of course …

At a practical level, it is often rather hot. Hardy (1887) mentioned the buildings being steeped in afternoon stagnation, while Mark Twain (1892) described a Florentine sunset as a sight to stir the coldest nature, and make a sympathetic one drunk with ecstasy. You get the gist: Florence stirs people to superlatives, and exultation.

This ecstatic condition has a name, Stendhal’s syndrome, a form of psychological breakdown when overwhelmed by the city’s richness of great art. Stendhal (pen name of the French fiction writer Marie-Henri Beyle) wrote of his visit in 1817:

“I was in a sort of ecstasy from the idea of being in Florence… I was seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart… the well-spring of life was dried up within me, and I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground.”

Fortunately, we avoided such full-blown panic attacks, though at times, we did feel ‘blown away’ and occasionally wondered if we could truly absorb any more of the amazing wall-to-wall portrayals of Madonnas and mortified Christs, a term I borrow from David Leavitt (2002). The sheer scale of its sublimity is staggering. Yet, somehow it all hangs together. Mary McCarthy in 1959, describing the Piazza della Signoria, made the valid point that there is no disharmony, despite the collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, Renaissance art, mannerist sculptures, and even nineteenth century additions. She is right, but I would extend that to entirely include the city’s central area, a glorious, harmonious potpourri of history that somehow makes astonishing aesthetic sense.

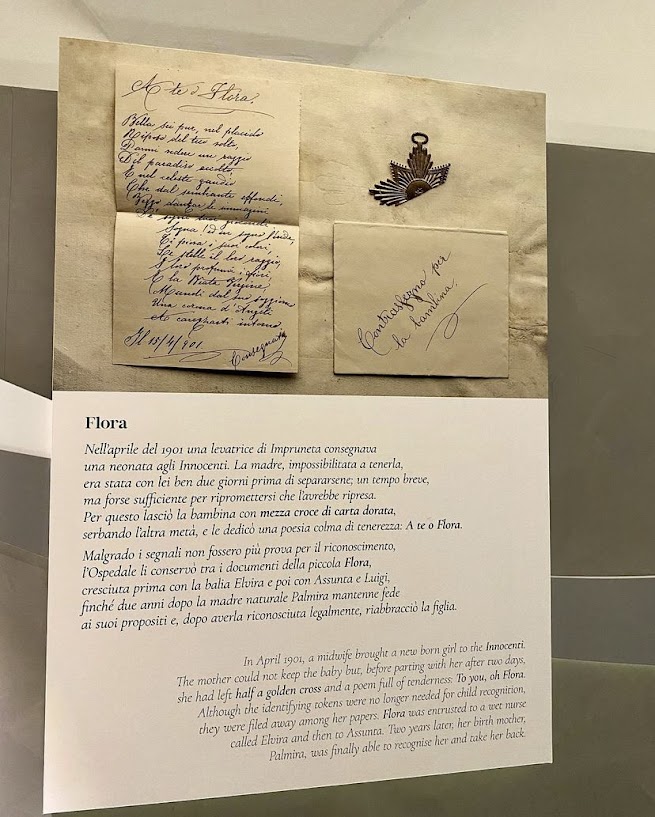

It is as if Florence was dreamed up by some super-talented town planner drawing inspiration from across the centuries. The closest to that was the aforementioned awesomely gifted master of linear perspective, Brunelleschi (1377-1446) who was so incredibly influential across the city all those centuries ago, and a man I would have been keen to talk to at my imaginary historical dinner table.

He looks such an ordinary fellow cast here in marble, yet this divine genius was one of the great minds of the Renaissance and was mourned across the city after his death (with indescribable grief, according to the artist and writer, Giorgio Vasari).

Are there any negatives to Florence? The answer is probably that there is relatively little green space in the centre, for obvious reasons. For anyone desperate for the open air, try the Parco Delle Cascine (reached by the number 17 bus) or via a walk alongside the Arno. It is Florence’s largest park, built originally as a farm estate (hunting and pigs) for the Medici, 118-160 hectares in size (depending on who you believe), one of the largest parks in Europe. You can certainly find trees here: elms, horse chestnuts, poplars and pines.

Literary links

Florence attracts creatives; it is mentioned in books ranging from Forster’s A Room With A View to Harris’s Hannibal.

For my visit, I prepared myself by reading a couple of titles by Ross King who writes in a heavily detailed manner. Brunelleschi’s Dome is short but fascinating, while his much longer The Bookseller of Florence: Vespasiano de Bisticci is captivating in its account of a Renaissance bibliophile, a tale of political rivalries, bookmaking and the rise of technology.

Even Dickens visited fabulous Florence when he wasn’t writing about poverty in London, and who could blame him for seeking out such elegance? He penned: “Among the four old bridges that span the river, the Ponte Vecchio, that bridge which is covered with the shops of jewellers and goldsmiths, is a most enchanting feature in the scene. The space of one house, in the centre, being left open, the view beyond, is shown as in a frame; and that precious glimpse of sky, and water, and rich buildings, shining so quietly among the huddled roofs and gables on the bridge, is exquisite.“

Alas, Dickens’ bridges across the glistening River Arno were bombed in August, 1944 (La Notte dei Ponti) by retreating Nazi soldiers, with only one remaining, the symbolic (and as Dickens said, enchanting) Ponte Vecchio, awash now and in the past, with jewellery shops, dripping with (surely unwearable) heavy gold or oro pesante.

Some say it is haunted. Obviously, if any place is, this should be.

So, Florence, Firenze.

Religious ritual

I am unashamedly lost in a strange, crowded world, imagining Dickens wandering around this glorious city, just as Brunelleschi, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Donatello, Galileo, Dante, Machiavelli and Gucci (along with many others, including most of the English Romantic poets) did before and after him. It feels surreal to be in such a place, with the makings of a whole dinner party of remarkably interesting guests. It is, as someone, somewhere wrote, impossibly beautiful.

Obviously, the crowds flock to the popular haunts, such as the dramatic Duomo (brainchild of Brunelleschi) and the impressive Uffizi gallery, designed by Vasari, which houses ancient Roman and Greek sculptures, and art collections with masterpieces by the Renaissance ‘big guns’, such as Botticelli’s famous The Birth of Venus and Primavera; and Caravaggio’s inebriated Bacchus and haunting Medusa. It is an overwhelming, unabashed ‘celeb-fest’ of the major artists of the time, and it is quite astonishing to walk in their city, effectively in their steps.

The religious theme to the artworks is ubiquitous with more Madonna and child variations than I ever expected to see in one lifetime, housed alarmingly close to brutal sculptures of torment and cruelty.

Catholicism was central here, and they have the art to prove it. Now, there is greater diversity of belief (or non-belief), with Catholics numbering only around 17 per cent of those practising a religion. Nonetheless, Catholic rituals persist. During the Renaissance, the city is said to have had 110 churches, so (without entering into the politics of it) Catholicism’s impact has been enduring.

We were fortunate to be in Florence for Easter, visiting the Duomo to see the Explosion of the Cart (Scoppio del Carro), a ritual dating from 1622. It relates to the influential Pazzi family and the Crusades (more detail here). Such were the crowds, we only had a sideways view, but nonetheless the fireworks were spectacular and many spectators were presented with spring flowers/olive branches.

The Archbishop of Florence, high-ranking Cardinal Guiseppe Betori, blessed people present at the service as he walked. Highly educated but also very traditional (he would spark fierce debate at the imaginary dining table), he once escaped an assassination attempt. At this year’s ritual, he seemed cheerful and was finely dressed in full regalia.

I was one of the many blessed but the following day was ‘the day of the stolen passport’, so maybe I was not quite blessed enough.

Incredible Churches

We all have favourites when it comes to Florentine churches; mine include:

Santa Spirito is a church on the other side of the Arno, whose stark facade hides its incredible interior containing thirty-eight (some say more) side chapels, many containing noteworthy artworks.

The architecture is said to be Brunelleschi at his best or at least his most authentic, his design reflecting not only the need for visual appeal but also to create a stage for the ‘actor’ priest to perform his rituals. Described as cavernous but harmonious, the ‘in your face’ (my term) baroque high altar was added later (early seventeenth century). I agree with its critics, that it is notable but its fussiness does not quite fit (but then baroque is generally way too elaborate and ornate for me).

Imagination fired, I enjoyed mentally re-creating the ‘battle of the pulpits’ between the prior, Savonarola (of Ferrara), who was said to be a spellbinding visionary firebrand of a preacher (imagine hearing him!) and his numerous opponents (such as Pope Alexander VI, a pleasure-seeking Borgia) who did not want to hear about their own loose morals and the hellfire of eternal damnation. Obviously, with such a sticky reputation, the ascetic Dominican friar, Savoranola, who had the sheer gall and guts to criticise the papacy, clerical corruption, and the excesses of the Roman Catholic Church, came to a terrible end in 1498 (aged 45) with his ashes scattered in the Arno. His followers were called ‘snivellers’ because he appeared anti everything that Renaissance Florentines held dear: jokes, luxuries, gambling, nude paintings, frivolity, sex (especially homosexuality) … the list was close to endless. Many will have heard of his ‘bonfire of the vanities‘ … but I cannot quite forgive him for burning books.

In fairness, however, puritanical Savonarola is often mooted as the precursor to the Protestant Reformation, with his emphasis on individual faith, compassion for the poor, and the authority of scripture above man. Also, on the plus side, my ‘A’ level in Tudor and European history did me proud, as I recalled quite a bit of information about this Renaissance/Reformation period …

I digress …

The sacristy at Santa Spirito is well worth the few euros requested, as you then see the wooden crucifix (Crocifisso) sculpture by a young Michelangelo, which takes centre stage. No photos are allowed in the church or sacristy, but the beautifully tranquil adjoining courtyard is quite another matter.

Back across the Arno, from the outside (station side) the Santa Maria Novella church also looks reasonably ordinary, though the Piazza aspect is far more ornate . Accessed via the tourist information centre, the building opens up into superb cloisters adorned with frescoes. It also houses Giotto’s realistic crucifix in the centre of the central nave. Its detail is fine, from the waves in Christ’s hair to the blood on his body, a dramatic portrayal of His pain and suffering, so much so that young artists were sketching/emulating it during our visit. The church is vast and the layout is said to be the work of Brunelleschi (again).

The Basilica of San Lorenzo, meanwhile is also sizeable, the parish church of the rich and powerful Medici family and another ‘must-see’. Yes, obviously, Brunelleschi was involved again (he is winning hero status in my mind) and the New Sacristy was built by Michelangelo.The cloister and loggia are wonderful, but the main attraction is the sublime area housing the Medici Chapels, a mind-blowing tomb created for the greater members of the Medici family. Its octagonal structure is completely covered with bronze, marble and hard stones. No one can enter this room and not simply stare in jaw-dropping awe. It is probably as close as I came to Stendhal’s syndrome!

The Church of Santa Croce is undergoing restoration work in places (Giotto’s frescoes, for example). It is the largest Franciscan church in the world, and contains four thousand art works, including Gaddi’s magnificent high altar, Vasari’s Last Supper, works by a young Donatello (including his life-size Crucifix) and a number of tombs of the ‘great and good’ (or even not so good – does the end really justify the means?) including Michelangelo, Machiavelli, Galileo, Alfieri, Foscolo and Rossini and the monuments to Alberti, Dante and Florence Nightingale. A friar kindly explained that Donatello’s wooden (carved from a single piece of wood) Crucifix was a departure from previous ones, as it was a more realistic depiction of Christ’s suffering (interestingly, it was also criticised for being unidealised). Donatello’s friend, Brunelleschi, was not impressed (love these little intellectual/creative feuds) saying:

It appeared to him that Donato had placed a ploughman on the Cross, and not a body like that of Jesus Christ, which was most delicate in all its parts.

Donatello challenged his friend to do better, which he did, in his Christ in Santa Novella, which is said to perfectly proportional.

Sadly, the basilica at Santa Croce was seriously damaged in the awful flood of 1966 when the Santa Croce neighbourhood was completely submerged, not just by water but also sludge, fuel oil, and detritus. 70,000 homes and 6,000 commercial properties were destroyed, but also 850 works of art, many irretrievably. (Read more here.)

Worthwhile visits …

Many other remarkable buildings are, amazingly, not churches, such as the imposing Pitti Palace, symbolising the Medici power over Tuscany. It later also housed the Habsburgs, and the Kings of Savoy, so three dynasties in total. The name (which I somehow kept calling ‘pretty’) came from its first owner, a banker called Luca Pitti, set at the foot of the Boboli hill beyond the Arno, after which the Italianate gardens are named. Much of the Palazzo was sadly closed when we visited, such as the Royal Apartments and the Museum of Costume and Fashion. Below is a painting by Bronzino of Nano Morgante, the court jester, who appeared to be quite a character – there are life paintings of his front and back, plus a sculpture of him riding a tortoise.

The gardens of the Pitti Palace, are stepped and terraced, based on symmetry, not gardens as the English would imagine them; if you are expecting thousands of pretty flowers, look away. However, there is an incredibly glorious grotto which compensated for the well-planned (but not so beautiful) gardens at the palace. The Grotte di Buontalenti or Grotta Grande is well worth a look, a home to scenes of stalactites, stalagmites, and marble mosaics. It is like walking into a real-life fairy tale, bizarre and bewildering, based around the manipulated Mannerist architecture, which I had to look up, and which seems to mean design characterised by artificiality, elegance and sensuous distortion of the human figure (The Tate). Its original construction dates from the 1500s.

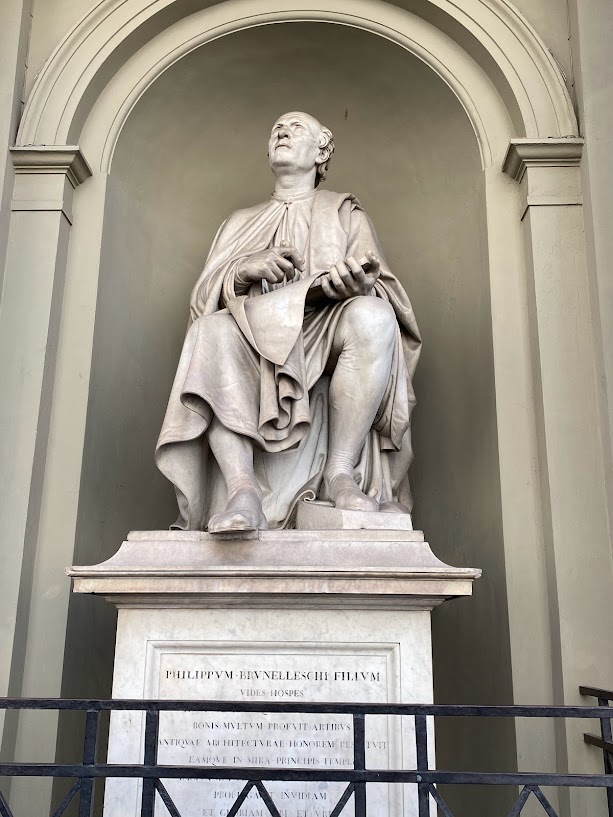

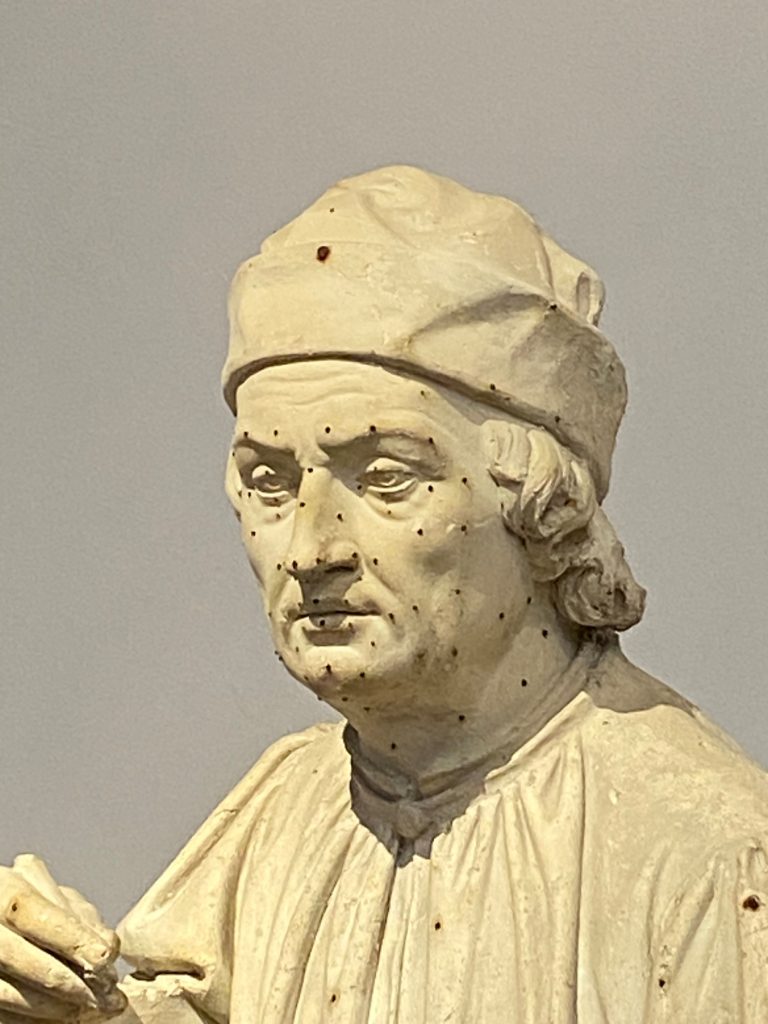

One of the most moving visits was to the Ospedale degli Innocenti. Architecturally attractive, it was also ahead of its time in caring for infants and children who were orphaned or abandoned (usually by desperate mothers whose babies were illegitimate). Anonymity was guaranteed and babies were left in a pila (basin) which was later replaced by a rota, a rotating stone. They were baptised and fed by wet nurses.

The boys were taught to read and write and later, were put up for adoption, usually as apprentices to craftsmen, or they entered the Church. The girls were placed as household servants or set to work in silk or wool production, washing and weaving cloth, while some became nuns. Some later received dowries if they found a marriage partner. Parents often left their baby with a unique medallion or keepsake of some kind so that they might one day be reunited with their child (in some cases, this actually happened), the details of which were meticulously recorded. Given it opened in the 1400s (built and managed with philanthropic money from the Silk Guild) it was incredibly forward-looking, a humanistic arm to the Renaissance. If you think too hard about it, then it becomes distressingly poignant.

If it does not bring a tear to your eyes, think harder.

Brunelleschi was once again involved in the building; he allegedly tried to create harmonious surroundings. I’d say he succeeded. The building (now a UNICEF global research centre) also contains a gallery containing fine paintings along with two roundels containing bambini sculptures. The blue terracotta roundels, with reliefs of babies stand out in this early Renaissance structure but it is the narratives within that have the most impact. Sometimes, words work even better than pictures.

There is so much more to see, and the Galleria Dell’Accademia is obviously a must-see for the beautiful marble sculpture of David (which became controversial only this year) along with many other statues, including some by the nineteenth century’s Lorenzo Bartolini. Many of the sculptures still have nail marks for accuracy. Do go, you will be blown away.

And then there is the food …

Remember: Italy will never be a normal country. Because Italy is Italy. If we were a normal country, we wouldn’t have Rome. We wouldn’t have Florence. We wouldn’t have the marvel that is Venice.

Matteo Renzi