Here’s one written when my mother was still alive and which I’ve since updated …the experience I describe here became a distant memory as my mother’s vascular dementia progressed.

Dementia is a demon who created a woman I disliked, dreaded seeing, but felt duty-bound to so do, who had me frequently in tears with her downright nastiness, but later also created a bewildered yet calm person I could once again care about, living in another world, another time. It enabled me to make peace with her prior to her death in 2017.

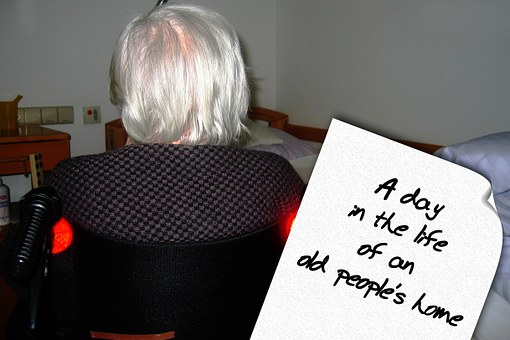

Since originally writing this, my father, following a stroke and the onset of Alzheimer’s also left his home and received nursing home care, surviving the Covid pandemic but dying at 93 in 2021. They used to compete to see who would die first. Well, Mum, you won! Unbeknown to either of them, my older brother beat them both to it, dying from Multiple System Atrophy in 2015. He was 61.

I wrote the following when Mum was still at home: she was vitriolic, hateful, and physically strong; if a malevolent stare could kill I would have dropped down dead on the spot. One day, I travelled from Devon to Birmingham to see her. She gave me that look. After five minutes of her time, she politely asked: “would you please leave now?” I did, hitting the German market and the Gluhwein!

It was extremely challenging for everyone, including her.

Damnable Dementia

Can you imagine having to change your mother’s urine-sodden underwear that she is convinced is wet because she has just washed it?

Or rinsing out her slipper where the urine caught it after dripping down her trouser leg?

Perhaps listening to your octogenarian parents talking in no uncertain terms – and graphically – about sex is more of a sticking point than the physical.

Or maybe it’s the personal insults they sling at you in a truly uninhibited fashion. The swearing. And the bile. “Who are you? I don’t f*cking know you”.

For me, it’s the urine and total loss of personal hygiene in a person whose house used to be so clean you really could have eaten off the floor. Now, the place smells unpleasant.

Incontinence isn’t necessarily part of dementia but it frequently becomes one of the many distressing symptoms: confusion, getting lost, struggling with words, forgetting things, mood swings, personality change or exaggeration, low attention span, poor mobility, delusion….the list is endless.

Every sufferer will vary in terms of symptoms, both their severity and type.

My parents live two hundred miles away and I see them infrequently because an hour of my company has long been more than enough for my father (10 minutes now suffices with my mother) yet I remember the days when my mother would spend at least an hour on the phone. They don’t/can’t use the phone these days. Those days have long gone. If the phone rings, Dad is more likely to tear it from its socket than answer it. Of course, in the early days, they were prey to all kind of sales scams by those parasites preying on the elderly; they were ordering £1000 chairs – and other things – by the blessed ‘phone. Such a nice man …

And to be honest, now, if they were not fed, watered and cared for, they would not survive. My mother’s dementia is advanced, so she is in a nursing home, or hospital, depending on how ill she is at any one time…Dad has three carers coming in each day, plus relatives.

Dementia – progressive confusion – is a subject people rarely think about until it personally impacts them. So it was with me. It is only now that my parents have well-advanced memory and communication problems that I am seeking and finding more information about this progressive condition which, according to the Alzheimer’s Society, affects hundreds of thousands of mainly elderly people in the UK.

‘Dementia’ is the set of symptoms affecting reasoning, and mood, among other things, which may have various causes. My mother, for example, has had nearly ten years of vascular dementia caused by problems of blood supply to the veins, commonly caused by diabetes and high blood pressure, or mini-strokes, although I have been minded to look more closely at Lewy dementia, after being alerted to the condition. I often wonder if her adult-lifelong addiction to anti-depressants played a part.

Alzheimer’s is the most common problem affecting around 496,000 people in the UK.

The scale of the problem is really quite scary, especially once people reach their 80s, where 1 in 6 of people, already vulnerable because of other infirmities, are affected.

31% of the population, according to a 2011 NHS study, fear dementia more than death or dying, and who can blame them for it is a slow and lingering death.

We are in a country which has over 750,000 dementia sufferers, yet to keep some perspective, it equates to 170 people per thousand aged 80 or above, meaning 830 octogenarians per thousand will not suffer it!

It has become the subject of a Government campaign, as ways to deal with a costly ageing population are discussed, but there are scary regional variations in dementia diagnosis rates with the Alzheimer’s Society telling us that diagnosis is as low as 31.6% in East Yorkshire and as high as 75.5% in Belfast.

It’s been an interesting journey for me because I have not yet been a primary carer for people with Alzheimer’s or dementia. That task has fallen to my brother who describes it as ‘being responsible for these bodies whose personalities bear little resemblance to the parents we once knew’. And my sister-in-law who, by rights, should not have to deal with it at all. Now my brother is also ill. The difficulties increase.

The Alzheimer’s Society talks of a sense of grief and bereavement, which I believe to be the hardest part for the family of the sufferer. Certainly, there is a very real sense of loss, many seeing it as an ongoing and living bereavement. Or a double loss. Yet, it is astonishing how many people carry the burden of dementia with them, and how few of us can see any joy in it.

It seems to be music and literature that has helped me more than any serious study. After all, any research will not now help my parents who have succumbed to this cruel disease which drags on and on, then on some more.

For example, every time I listen to the Amy MacDonald song “Left That Body Long Ago”, I cry. The lyrics that especially get the tears flowing are those about losing the person, but also that it isn’t the end, it’s merely goodbye. The end can seem like a long way off.

But it also helps to get into the mindset of the sufferer, something we can only imagine because, let’s face it, no one really knows how someone with advanced dementia feels. It is heartening to think that there maybe is some happiness within, somewhere. But I’m not sure how accurate that is. Something I discovered from a couple of MOOCs on the subject as that the benefit of touch is much greater than of talk.

Reading novelist Lisa Genova’s book ‘Still Alice’ about early-onset Alzheimer’s was also a revelation in terms of the sense of the gradual development of the disease and the diminishing sense of awareness in the sufferer.

The harsh reality remained that when I set off to see my parents for a pre-Christmas visit two years ago, their diminished state, the heightening of their personality traits (especially the negative ones) and their inability to care for themselves, would hit deep and hard. It did. They were unkempt, as usual (despite family and professional care) and vitriolic and argumentative as usual, with language and innuendo that could make a navvy blush, and which led to many a complaint from their carers.

What surprises me is that so many people experience dementia in the family, but that so few talk about it, until it crops up in passing. It is almost the last taboo.

Yet, it can affect anyone, from the most intellectually capable through the most physically active to the person who has spent much of their life watching TV.

For the sufferer, dementia is bad enough, For the family, it is a huge loss, without the chance to grieve.

And the most sobering thought of all is that it could happen to any of us: you or I.